Learn Mandarin Chinese

Progressive self study course for absolute beginners to intermediate learners

Progressive self study course for absolute beginners to intermediate learners

There are over 400 lessons to choose from. Absolute beginners should start at lesson 1. Each lesson continues where the last one left off.

Later lessons use the Chinese that was taught in earlier lessons. This way you are constantly reusing and remembering what was taught.

Premium subscribers get access to exercises, games and flashcard activities to reinforce what was taught.

Sign up with your Facebook account to try out the first 4 lessons of the course for free.

This post could act as a counter to the "Is Chinese Really That Hard?" post. One aspect of Chinese that it took me some time to grasp was that meanings in Chinese and English don't always exhibit a one to one relationship. In the beginning, each time I came across a new word in Chinese, I would look for the English equivalent. That worked fine for common nouns - boy, girl, China, America, but then I started to discover that some words had overlapping meanings between Chinese and English.

Many words have multiple meanings. I learned early on that yīnggāi means "should." Simple enough I thought, until one day when someone looked at me and said Nǐ yīnggāi shēngbìng le. "You should be sick"? I thought. Why should I be sick?? That's when I learned that it also has a meaning of "must" as in "You must be sick." Ok, easy to fathom - it has multiple meanings, just like many words in English.

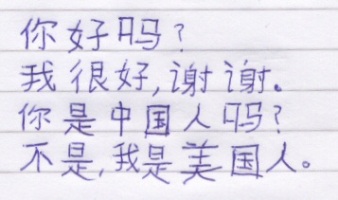

I then came across words that describe different levels of intensity than their equivalent English counterparts. One of the first words I learned - hěn was taught to me as meaning "very" in English. So to answer Nǐ hǎo ma? you answer Wǒ hěn hǎo as in "I'm very good." But what if I wasn't very good? What if I only wanted to answer "I'm good"? Logically that should be Wǒ hǎo. But that was wrong. You had to have the hěn in there, since it actually is a less intensive "very" than its English counterpart. To really answer "I'm very good" you would say Wǒ fēicháng hǎo. Never mind that the dictionary describes fēicháng as meaning "extremely" since its actual intensity lies somewhere between "very" and "extremely" in English.

This creates an interesting situation where it's possible to describe situations in different degrees in Chinese than in English. For example many teachers are described as being hěn xiōng. Yet if you look up that word in the dictionary you get a meaning of being "fierce" or "terrible." Hardly words I would use to describe an ordinary teacher (although there undoubtedly are extreme examples who could fit that category). At first I assumed "strict" or "stern" might be a better definition but there are other words in Chinese to describe those terms, so at some point you have to give up on looking for an exact definition since there isn't one.

For an exercise in futility, you can skim through words in a Chinese-English dictionary to look at all the extraneous definitions (great way to pass the time). Take a look at the variety of definitions for the following words:

Jiāo - to deliver / to turn over / to make friends / to intersect (lines) / to pay (money)

Dōu - both / all / even / already

Jiù - at once / then / only / to approach / to undertake / already

Dài - band / belt / ribbon / tire / area / zone / region / to wear / to carry / to lead / to look after / to raise

Sòng - to deliver / to carry / to present / to see off / to send

So what is the solution to this mess? Learn new characters within context. Don't worry about extraneous meanings. Learn to use new words within the context you discovered them and master those current definitions before moving on to other usages. While the English meaning is great for getting your foot in the door, rely on examples in different contexts before being satisfied with a definition.

Many people regard Chinese as being one of the toughest languages to learn. That in itself might be reason enough to learn it, since many like the challenge that comes with it and relish the looks of amazement that passers by give when they hear that you can speak Chinese! In my personal experience however, I found that many of the reasons given for Chinese being so hard weren't actually that hard when broken down. This meant that I was learning a language that others thought was very hard, when actually that wasn't necessarily the case (much better than learning something that others think is easy but actually isn't!) Here are some of the main obstacles that people encounter when trying to learn Chinese, and my personal solutions to overcoming then.

The Tones

This is the initial challenge that most beginners face. How can mài mean "to sell" while mǎi mean "to buy"? So now, not only do you have to remember that shuì jiào means "sleep", you better remember that there are two fourth tones there or you risk talking about "dumplings" instead of "sleep." Surely having to memorize the extra tone element on top of each new vocabulary word would drive any learner crazy?

My solution: This issue here is usually enough to weed out most beginners, which is great for the rest of us (less people to share the stage with!). The trick here is that this is only a problem in the beginning. The more you expose yourself to the language, the more your brain will automatically fuse this element into your language learning until you get to the point where you unconsciously start recognizing the tones for new vocabulary. Compare these two scenarios:

Student: How do you say "United Nations" in Chinese?

Teacher: Lián hé guó

Student: "Lian he guo", ok. And what tones does that use?

Teacher: Three second tones.

Student: Got it, thanks!

Student: How do you say "United Nations" in Chinese?

Teacher: Lián hé guó

Student: Lián hé guó. Got it, thanks!

In the second scenario the student has automatically learned to associate tones with new vocabulary. If you were to ask him what the tones were, he would have to repeat the words in his mind first and pull the tones out from there, since the tones and the words are already associated together.

A great exercise to get to this level is mindless repetition of sentences from native speakers, so that you start to develop the ebb and flow of the language by yourself. As you listen to the podcasts in this course, use the pauses provided to repeat after the speaker, even with vocabulary you are already familiar with to get yourself in this mode.

The Writing System

This is of course a challenge for many, including native speakers themselves. One of the reasons given for the slowness in progression of Chinese learners is that because reading and writing takes so long to learn, we learners lose out from the experience of learning from reading. In English, if we come across a word we don't understand we can easily write it down and look it up later. How do we do that in Chinese when you come across a word you don't know that uses characters that are equally unfamiliar? How do Chinese speakers look up unfamiliar characters in a dictionary?

My solution:There are a couple of separate issues here. If it's just learning new vocabulary and language usage from reading you are looking for, there are plenty of pinyin resources out there, including on this website. Similarly, if you come across a new word in your learning, it's easy enough to write it down in pinyin and look it up in a pinyin dictionary. Learning characters of course is another story, and one that has been touched upon in other categories.

Grammar: This is an aspect of Chinese that is often neglected because it actually is much simpler than in other languages. The extra time put in learning to read and write is offset by the time you don't have to put in learning conjugations of verbs, tenses and other issues present in other languages. This can be a problem in itself since the lack of grammar rules makes Chinese very context sensitive. Sentences can have multiple meanings that may seem to contradict each other with only subtle clues to distinguish between them.

My solution: The answer here is the same as the answer for tones. Fortunately (or unfortunately for some), it's not something you consciously study or memorize to understand. You learn by getting the feel for the language from experience. Listen to enough podcasts, and get yourself experienced with enough dialogues and you'll slowly start to gather a "feel" for the language. You'll find yourself instinctively responding with the right expressions without even knowing how or why.

The road to fluency: When learning any language, you will find some aspects easier than others. This is a result of usage patterns. In my daily life, I find myself listening to a lot more Chinese than I speak. As a result my listening skills are greater than my speaking skills. Similarly my reading skills are more advanced than my writing skills. The nice thing about all of this though is that my fluency matches my level of requirement. My listening skills are greater because I have to do a lot more listening than speaking in my daily life. Similarly I rarely have to physically write anything in my daily routine (especially in this age of computers), whereas reading is more useful for me, so the latter skill is more developed.

There's no rule that says all skills have to be equal. Focus on the areas of importance for you and improve those areas first. Learning any language (or any skill for that matter) is only as hard as you make it out to be. Take advantage of the many tools available in this course and on the web to focus on your areas of weakness. Then gloat that you are able to do what so many others have failed or given up on doing. Jiāyóu!

Like most of you, when I first began learning Chinese, I was very fascinated with the thousands of Chinese characters out there and the methods that people used to learn them. As I began to learn them myself, I began to wonder how people were able to write so fast if there were characters that required so many strokes. Surely if there was a contest between someone writing a paragraph in English and someone writing the equivalent paragraph in Chinese, the former would easily win! However, upon closer examination, two things became evident. Firstly, the equivalent Chinese paragraph would be shorter (in terms of characters required) than its English counterpart. As well, just like in English, Chinese writers use their own form of short hand to greatly speed up their writing.

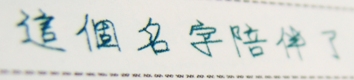

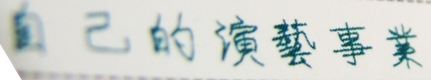

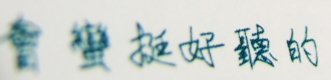

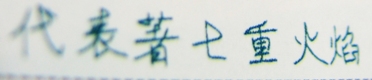

As you will see in the following examples, when handwriting in Chinese, strokes tend to be slurred. While to the untrained eye the end result for some characters may not look like the characters they are supposed to represent, native speakers can easily make them out. Compare the following with their typed equivalents.

這個名字陪伴了

自己的演藝事業

會蠻挺好聽的

代表著七重火焰

In the 1950s, to increase the literacy rate among its citizens, the government in mainland China began to develop a system of simplifying the thousands of Chinese characters, by decreasing the number of pen strokes required to write them. This resulted in the formation of two systems of Chinese characters - the traditional system (still used in Taiwan, parts of Hong Kong and many overseas communities) and the simplified system (used in mainland China and Singapore). As a student, you can choose which system to focus on, as our course supports both formats.

By choosing to learn the simplified version, you are shortening the amount of characters you need to learn, since many similar sounding characters have been replaced with a single one (for example while you have the characters 隻, 祇 and 只 in traditional, all three are combined into 只 in the simplified form). The characters you do have to learn also become a lot simpler, for example 嗎 becomes 吗 and 麼 becomes 么. The proponents for traditional form emphasize the beauty and tradition in the characters, many of which were developed in the fifth century. By learning the history behind characters, you also learn more about the culture and rationale behind the language.

In many cases, the simplified version of a character removes components from the original traditional character, thereby reducing the number of strokes required to write it. The traditional character for electricity for example 電 is made up of two components - rain, followed by lightning striking a field at the bottom (as depicted in the picture above). The simplified version 电 removes the rain component. Similarly, the traditional character to listen (聽) is a combination of "ear" (耳) and "goodness" (德). The simplified version however is reduced to 听, focusing more on the sound component than the origins of the character.

The debate then becomes whether it is easier to remember the smaller number of strokes of the simplified characters, or the meanings behind the components in many of the traditional characters. Other factors to consider include that most "writing" these days is done by typing out characters, in which case stroke count becomes meaningless. In the end, it comes down to where you are and how you plan to use your Chinese. Since literature written before the 1950s was all done in traditional characters, there will always be a need for scholars to learn the traditional system. However for learners predominantly in mainland China, focusing on current material, simplified may be the way to go.

The Mid-Autumn Moon Festival (zhōngqiūjié), or simply the Moon Festival, is celebrated in many countries throughout Asia, although it it originated some 3000 years ago in China. This festival falls on the 15th day of the 8th month in the Chinese lunar calendar. Just as Westerners may wish for a "white Christmas", Chinese wish for a clear sky on this day to observe the full moon in all its glory.

After Chinese New Year, the Moon Festival is the next important holiday in the Chinese lunar calendar. It is a legal holiday and is used to celebrate abundance and an end to the harvest season before winter kicks in, similar to why North Americans celebrate Thanksgiving Day. However, instead of eating turkey, traditional foods include moon cakes, which come in wide varieties, and the pomelo fruit. Traditions include lighting lanterns and having barbecues under the moonlight, topped off with fireworks to celebrate the occasion.

The story behind the celebration of the Moon Festival is similar to that of Chinese Valentine's Day. Once upon a time there were ten suns in the sky which began to scorch the earth, causing misery among the people. Houyi, the archer, solved the problem by shooting the suns down one by one, leaving just one. He was rewarded by becoming the king and marrying the beautiful Chang'e, as well as receiving a pill that granted immortality among the Gods. However, knowing that swallowing the pill would cause him to leave earth and go to the sky, he gave it to Chang'e to save for the future. One day, Chang'e was attacked by their servant who knew about the pill and wanted it for himself. Knowing that she had no other choice, Chang'e swallowed the pill herself, causing her to ascend into the sky and to the moon. Houyi tried to chase her, but in vain. Since then, every year during the moon festival, when the moon was at is brightest, Houyi would celebrate the memory of his love by lighting incense and eating the fruits and desserts that she loved to eat, which is how citizens today also celebrate the occasion.

I've always had a problem answering the question "Can you speak Chinese?" What exactly does the speaker mean by that question? Do you need to be fluent in the language to answer that question affirmatively? And if so, what level do you need to reach to attain "fluency"? To complicate things further, one's listening / speaking skills might be a lot more developed than their reading / writing skills, so how do you factor that into the picture?

You will find that as you learn a new language, there are certain levels of fluency that you come across. The hardest part is crossing from one level to another, as this is a jump that many don't make. The reasons for this vary from person to person, but in general we tend to get relaxed in our comfort zone. In the early stages, you learn enough to survive where you are. To get to the next level requires extra effort on your part which may affect your daily routine. Most would rather stay in their comfort zone than expend this extra effort.

I have noticed this resistance by analyzing feedback and statistics for the users of my course as we cross from one level to another. It would be a much more pleasant experience for basic listeners, for me to continue teaching the course in the format used in earlier lessons where a dialog is presented in Chinese, then explained completely in English. However, by adding Chinese to the explanations in later lessons, I am forcing the listener to consult the translations and word bank where necessary, which of course requires extra effort on their part.

During my recent experience working with individuals of this course, I also found it interesting that different users used different standards to decide when to progress to later lessons. Some students wouldn't continue unless they understood 90% plus of the material and vocabulary used in a lesson. Others were more lenient and would continue on despite much less retention. Of course there is also the question of what exactly you are trying to learn. For some, having proper pronunciation was most important. Others were more interested in vocabulary or grammar usage. Some might have mastered these skills and were now going through earlier lessons to shore up their reading skills.

I think it would be quite an accomplishment for a user to actually start the CLO course from the first lesson and be able to progress at their own pace all the way to the most recent lessons. Hopefully the tools we have added and will continue to add along the way will help users accomplish the individual goals and targets they have set for themselves. If there are certain hints or strategies that have worked well for you, please share them with the rest of us.

One of the lessons I found out early on during my initial stint in Taiwan was that there was more than one form of Chinese, in fact a LOT more! I found it odd that when people spoke to me, I could make out what they were saying, and they seemed to understand what I was saying to them. However, when I tried to eavesdrop on people talking to each other, more times than not, I couldn't understand a word of what they were saying!

We all know that Mandarin is the official language for China and Taiwan. However, each region within these places has their own unique dialect that can differ greatly from typical Mandarin. In Taiwan for example, most residents speak Minnanhua (also knows as Taiwanese) which is similar to the dialects spoken in the Fujian province of China. In fact, most regions in China have their own hua or local dialect. So when local residents speak to each other, that is usually the language they will use. It is what is used at home among family members as well.

Many generations ago, the Mandarins of Imperial China came up with an official language to unify the country and allow people from different regions to be able to communicate with each other. This is why Mandarin is called Putonghua (the common language) in Mainland China and Guoyu (the country language) in Taiwan. It is the language used to teach in school, on the news and to conduct business in (which makes it a good language to learn!)

Because for most people, Mandarin is formerly taught to them in school, it is also a sign of good education if you can speak proper Mandarin. So don't be surprised if someone compliments your Chinese by saying "It's very standard!" If you want to really fit in with the locals, learn a few words of the local dialect. If you think being able to speak a few words of Mandarin will impress them, imagine if you spoke a few words of the local language - that will be sure to floor them, as they know there are no books on the subject - the only way to learn it is to pick it up off the street, just like they had to.

As this course has shown, there are differences between pronunciation patterns from different regions in China. Learning about these dialects helped me better appreciate the differences in speech between different speakers. Just like it's possible to identify where a person comes from by their English accent, it is also possible to do so by listening to a person's Chinese.

While many may know that tea is popular in Chinese culture, many may not know how important and how integral it is as part of daily life. Tea is offered by the host to his guests as a sign of respect towards them. When visiting someone's house, expect to be served tea when you are first seated. Going to a business meeting? Expect to be served tea before and during the meeting. Getting a haircut? It's not uncommon for tea to be offered to you there as well. Tea ceremonies are also an integral part of Chinese weddings, where the new bride and groom offer tea to their parents and in-laws as a show of appreciation.

There are several different kinds of tea available, some more common than others, depending on the occasion. Green tea is a more natural form as it maintains the original color of the tea leaves. This flavor is found not only in tea but also in everything from chewing gum, medicines, cooking, soaps and even toothpaste! The green tea extract has many healthy properties, so it is common to extend these properties to other products of daily use.

Black tea (or red tea as it is known in Chinese) gets its color after fermentation of the tea leaves. Wulong tea is a cross between green and black tea, as a result of partial fermentation. Other types of tea include scented varieties such as jasmine tea, created by mixing flowers during the processing of tea leaves.

So why is tea so popular? In the summer, tea is known for dispelling heat and producing a cooling and relaxing sensation. Tea is also considered to have chemicals that aid in digestion, as well as removing nicotine and alcohol from the body. There is a fascinating process of how tea is served, involving constant pouring and repouring of hot water from the teapot to the teacups to provide the proper tea color and aroma. This process is especially used at tea shops, when customers are sampling different types of tea for purchase.

When served tea, it is best to follow the gestures that others around you use to show gratitude to the host, as these can vary from region to region. In general however, expect the host to make sure your tea cup is constantly refilled, so if you have had your fill, it is best to take a sip and let the rest sit in your cup.

Some may be scared off to learn that at one point there were as many as 50 000 different Chinese characters (by some estimates). Fortunately, this number has been whittled down to about 6500 for simplified computer fonts (double that for traditional fonts). That is still a big number for anyone to tackle, so the question becomes how many characters should a Chinese learner learn and how do you know which characters to learn?

The common standard to answer this question is to use a typical newspaper in Mainland China. Studies are regularly conducted to note which characters are most commonly used in printed media. To achieve 100% recognition of the characters used in a newspaper, you would need to know about 3000 characters (4000 for traditional characters in Taiwan). It is common to find dictionaries that only focus on these 3000 characters. So now that you know what the goal is, the question becomes how do you go about learning them? Do you just turn to page one of the dictionary and start learning a few characters per day? You could, but there is a much easier (and more efficient) way.

You only need to learn the 400 most commonly used characters to get to the level of 67% recognition. So it makes sense to study these 400 characters first, before moving on to the lesser used ones. Each time you see a character you know again, you are reinforcing that recognition pattern in your mind. Additionally, the process becomes easier, since in the process of learning, you will also be learning the radicals involved, so new characters will just involve modifying characters you already know, rather than having to learn them from scratch. Once you get to this magic 400 mark, you can then work on learning the next 600 characters, which will get you all the way to 88% recognition level.

As easy as this sounds, many study materials out there DON'T use this concept. A quick glance at a couple of textbooks teaching how to write characters showed one teaching the character for dragon (the 659th most common character), another teaching the character for fire (427th most common) and another teaching the character for busy (672nd most common). And this was the first lesson! It is easy to see why many students may give up learning how to read and write, when having to use methods like this.